The content, consistency, and predictability of U.S. policy shaped the global order for eight decades, but these lodestars of geopolitics and geoeconomics can no longer be taken for granted. What comes next will be determined by the ambitions and actions of major powers and other international actors.

Some have predicted that China can and will reshape the global order. But does it want to? If so, what will it seek to preserve, reform, or replace? Choices made by China and other regional states will hinge on their perceptions of future U.S. behavior — whether they deem it more prudent to retain key attributes of the U.S.-built order, with America playing a different role, than to move toward an untested and likely contested alternative — and how they prioritize their own interests.

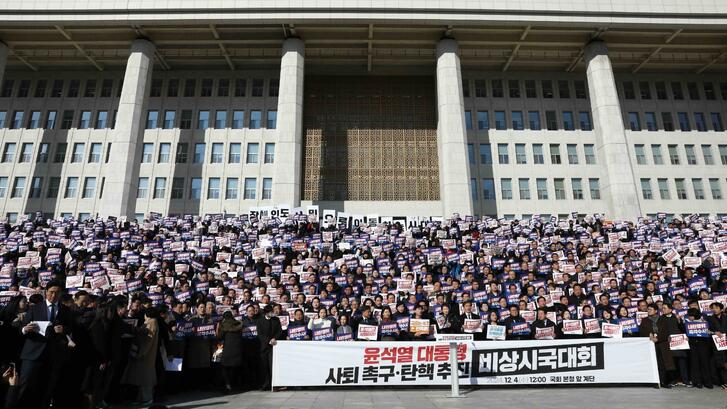

This year’s Oksenberg Conference will examine how China and other Indo-Pacific actors read the geopolitical landscape, set priorities, and devise strategies to shape the regional order amid uncertainty about U.S. policy and the future of global governance.

PANEL 1

China’s Perceptions and Possible Responses

Moderator

Thomas Fingar

Shorenstein APARC Fellow, Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Stanford University

Panelists

Da Wei

Professor and Director, Center for International Security and Strategy, Tsinghua University

Mark Lambert

Retired U.S. Department of State Official, Formerly China Coordinator and Deputy Assistant Secretary

Susan Shirk

Research Professor, School of Global Policy and Strategy, University of California San Diego

PANEL 2

Other Asia-Pacific Regional Actors’ Perceptions and Policy Calculations

Moderator

Laura Stone

Retired U.S. Ambassador and Career Foreign Service Officer; Inaugural China Policy Fellow at APARC, Stanford University

Panelists

Victor Cha

Distinguished University Professor, D.S. Song-KF Chair, and Professor of Government, Georgetown University

Katherine Monahan

Visiting Scholar and Japan Program Fellow 2025-2026, APARC, Stanford University

Kathryn Stoner

Satre Family Senior Fellow, Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Stanford University

Emily Tallo

Postdoctoral Fellow, Center for International Security and Cooperation, Stanford University

Victor Cha is Distinguished University Professor at Georgetown University and President of the Geopolitics and Foreign Policy Department at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. He previously served on the Defense Policy Board for the Biden administration and on the National Security Council for the George W. Bush administration. He is the award-winning author of nine books including The Black Box: Demystifying the Study of Korean Unification and North Korea (Columbia, 2025). His newest book is China’s Weaponization of Trade: Resistance Through Collective Resilience(Columbia, January 2026) with E. Kim and A. Lim. Dr. Cha received his PhD, MIA, and BA from Columbia University and a BA with honors from Oxford University.

Da Wei is the director of the Center for International Security and Strategy (CISS) at Tsinghua, and professor of department of International Relations, school of Social Science, Tsinghua University. Dr. Da ’s research expertise covers China-US relations and US security & foreign policy. Da Wei has worked in China’s academic and policy community for more than 2 decades. Prior to current positions, Dr. Da Wei was the assistant president of University of International Relations (2017-2020), director of the Institute of American Studies, China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (2013-2017). He has written hundreds of policy papers to Chinese government, and published dozens of academic papers on journals in China, the US and other countries.

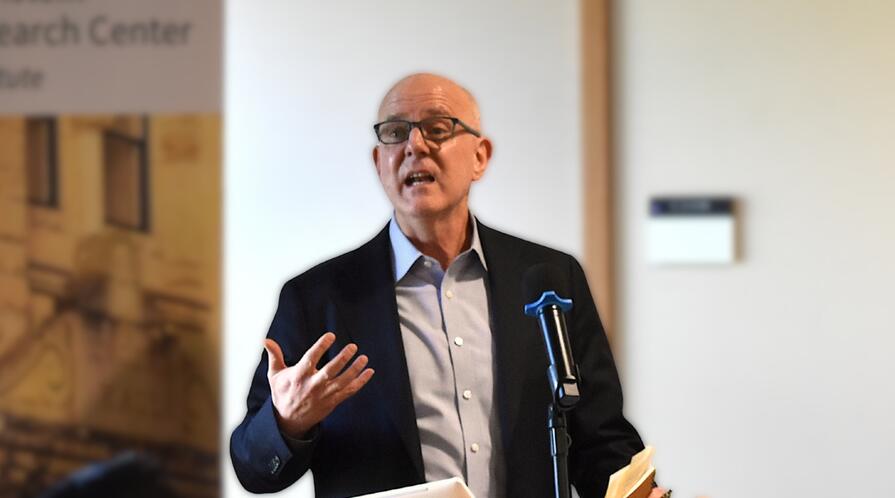

Thomas Fingar is a Shorenstein APARC Fellow in the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. He was the inaugural Oksenberg-Rohlen Distinguished Fellow from 2010 through 2015 and the Payne Distinguished Lecturer at Stanford in 2009.

From 2005 through 2008, he served as the first deputy director of national intelligence for analysis and, concurrently, as chairman of the National Intelligence Council. Fingar served previously as assistant secretary of the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (2000-01 and 2004-05), principal deputy assistant secretary (2001-03), deputy assistant secretary for analysis (1994-2000), director of the Office of Analysis for East Asia and the Pacific (1989-94), and chief of the China Division (1986-89). Between 1975 and 1986, he held several positions at Stanford University, including senior research associate in the Center for International Security and Arms Control.

Fingar is a graduate of Cornell University (A.B. in Government and History, 1968) and Stanford University (M.A., 1969, and Ph.D., 1977, both in political science). His numerous publications include the most recent book, From Mandate to Blueprint: Lessons from Intelligence Reform (Stanford University Press, 2021).

Mark Lambert is a retired State Department official. He served as China Coordinator and Deputy Assistant Secretary in the Bureau of East Asia and Pacific Affairs. He oversaw the Office of China Coordination and the Office of Taiwan Coordination. Mark has extensive experience in China, cross-Strait, and Asia Pacific affairs. He served as Deputy Assistant Secretary with responsibility for Japan, Korea, Mongolia, Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands. Earlier he established the International Organizations Bureau’s office aimed at protecting UN integrity from authoritarianism and served as Special Envoy for North Korean Affairs. Previously, he was named the State Department’s human rights officer of the year for devising a strategy to release Chinese political prisoners and promote religious freedom.

Katherine Monahan is a visiting scholar and Japan Program Fellow for the 2025-26 academic year. Ms. Monahan has completed 16 assignments on four continents during her 30 years as a Foreign Service Officer with the U.S. Department of State. She recently returned from Tokyo, where she was Deputy Chief of Mission at the U.S. Embassy in Japan, following roles as Charge d’affaires for Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu, and Deputy Chief of Mission to New Zealand, Samoa, Cook Islands, and Niue. She was Director for East Asia at the National Security Council from 2022 to 2023. Previously, she worked for the U.S. Department of the Treasury in Tokyo as Economic, Trade and Labor Counselor in Mexico City, Privatization Lead in Warsaw after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Advisor to the World Bank, and Deputy Executive Director of the Secretary of State’s Global Health Initiative, among other roles. As lead of UNICEF’s International Financial Institutions office, Ms. Monahan negotiated over $1 billion in funding for children. A member of the Bar in California and Washington, D.C., Ms. Monahan began her career as an attorney in Los Angeles.

Susan Shirk is a research professor at the UC San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy and director emeritus of its 21st Century China Center. She is one of the most influential experts working on U.S.-China relations and Chinese politics. She is also director emeritus of the UC Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation (IGCC). Susan Shirk first visited China in 1971 and has been teaching, researching and engaging China diplomatically ever since. From 1997-2000, Shirk served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of State in the Bureau of East Asia and Pacific Affairs, with responsibility for China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Mongolia. Her current book is "Overreach: How China Derailed Its Peaceful Rise". Other books include "China: Fragile Superpower," which helped frame the policy debate on China in the U.S. and other countries. Her other publications include "The Political Logic of Economic Reform in China"; "How China Opened its Door"; "Competitive Comrades: Career Incentives and Student Strategies in China"; and her edited book, "Changing Media, Changing China."

Laura Stone is a retired Ambassador and career foreign service officer. She was APARC's inaugural China Policy Fellow and a Lecturer at the Center for East Asian Studies. She previously served as the Deputy Coordinator of the Secretary of State's Office of COVID Response and Health Security, responsible for assisting in coordinating the global diplomatic response to the COVID pandemic; the Deputy Assistant Secretary for South Asia overseeing U.S. policy towards and relations with India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Maldives, and Bhutan; Special Advisor to the Undersecretary of State for Economic Growth; and the designated Deputy Assistant Secretary for China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Mongolia. She has worked as the Director of the Office of Chinese and Mongolian Affairs; Director of the Economic Policy Office in the Bureau of East Asia and Pacific Affairs; and Economic Counselor in Hanoi, Vietnam. She served three tours in Beijing as well as tours in Bangkok, Tokyo, the Public Affairs Bureau, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and the Bureau of Intelligence and Research.

Kathryn Stoner is the Mosbacher Director of the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law (CDDRL), and a Senior Fellow at CDDRL and the Center on International Security and Cooperation at FSI. From 2017 to 2021, she served as FSI's Deputy Director. She is Professor of Political Science (by courtesy) at Stanford and she teaches in the Department of Political Science, and in the Program on International Relations, as well as in the Ford Dorsey Master's in International Policy Program. She is also a Senior Fellow (by courtesy) at the Hoover Institution. Prior to coming to Stanford in 2004, she was on the faculty at Princeton University for nine years, jointly appointed to the Department of Politics and the Princeton School for International and Public Affairs (formerly the Woodrow Wilson School). At Princeton she received the Ralph O. Glendinning Preceptorship awarded to outstanding junior faculty. She also served as a Visiting Associate Professor of Political Science at Columbia University, and an Assistant Professor of Political Science at McGill University. She has held fellowships at Harvard University as well as the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, DC.

Emily Tallo is the India-U.S. Security Fellow at the Center for International Security and Cooperation. Before coming to CISAC, Emily was a PhD candidate in political science at the University of Chicago specializing in international relations. Prior to starting her Ph.D., she was a research assistant in the Stimson Center’s South Asia program. Emily's research agenda stems from a deep interest in how political elites influence foreign policy through their interactions with other elites. Although leaders make the final decisions in international politics, they must contend with the interests of foreign policy elites such as advisers, politicians, and bureaucrats. Her book project explores how political leaders shape foreign policymaking institutions, rules, and norms to achieve their policy objectives despite real or anticipated resistance from the foreign policy bureaucracies. Emily's other projects relate to how political elites structure foreign policy debates in democratic countries, especially in India.