Islamic Environmental Ethics and Multispecies Responsibility in Southeast Asia

This event is co-sponsored by the Sohaib and Sara Abbasi Program in Islamic Studies at Stanford Global Studies

Are references to religion in this time of climate crisis always cast in nostalgic or apocalyptic terms? This talk turns instead to everyday Islamic practices in Southeast Asia, asking how Muslims, and non‑Muslims in Islamic Southeast Asian contexts, have understood, experienced, and narrated their own times of ecological crisis, resource extraction, and rapid developmental change. It focuses on Islamic environmental sciences and on narratives about communities’ relationships with environments and more‑than‑human beings, relationships marked by care and reverence as well as violence and extraction. I consider how Islamic traditions in Southeast Asia have historically promoted both human‑centeredness and interspecies relatedness, and how these tensions have shaped environmental responses. In doing so, the paper asks how we might learn from Southeast Asian communities about environmental and multispecies responsibility, engaging their ethical grammars and local knowledge, while recognizing that Muslim communities—also implicated in ongoing environmental destruction—are important producers of concepts and practices for living responsibly with a damaged planet.

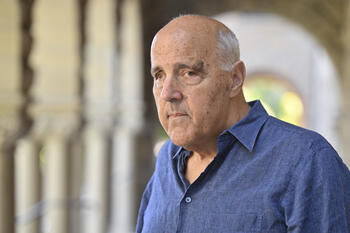

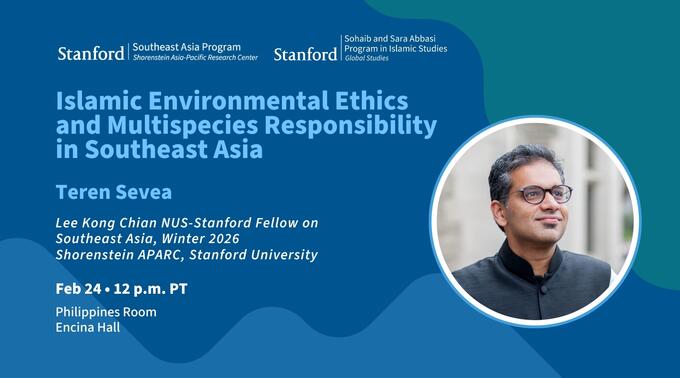

Teren Sevea joins the Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center (APARC) as visiting scholar and Lee Kong Chian NUS-Stanford Fellow on Southeast Asia for the winter quarter of 2026. He currently serves as Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Associate Professor of Islamic Studies at Harvard Divinity School.

He is a scholar of Islam and Muslim societies in South and Southeast Asia, and received his PhD in History from the University of California, Los Angeles. Before joining HDS, he served as Assistant Professor of South Asia Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Sevea is the author of Miracles and Material Life: Rice, Ore, Traps and Guns in Islamic Malaya (Cambridge University Press, 2020), which received the 2022 Harry J.Benda Prize, awarded by the Association of Asian Studies. Sevea also co-edited Islamic Connections: Muslim Societies in South and Southeast Asia (ISEAS, 2009). He is currently completing his second book entitled Singapore Islam: The Prophet's Port and Sufism across the Oceans, and is working on his third monograph, provisionally entitled Animal Saints and Sinners: Lessons on Islam and Multispeciesism from the East.

Sevea is the author of book chapters and journal articles pertaining to Indian Ocean networks, Sufi textual traditions, Islamic erotology, Islamic third worldism, and the socioeconomic significance of spirits, that have been published in journals such as Third World Quarterly, Modern Asian Studies, The Indian Economic and Social History Review and Journal of Sufi Studies. In addition to this, he is a coordinator of a multimedia project entitled “The Lighthouses of God: Mapping Sanctity Across the Indian Ocean,” which investigates the evolving landscapes of Indian Ocean Islam through photography, film, and GIS technology.

Questions?

Contact Kana Igarashi Limpanukorn

Teren Sevea

Teren Sevea joins the Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center (APARC) as visiting scholar and Lee Kong Chian NUS-Stanford Fellow on Southeast Asia for the winter quarter of 2026. He currently serves as Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Associate Professor of Islamic Studies at Harvard Divinity School.

He is a scholar of Islam and Muslim societies in South and Southeast Asia, and received his PhD in History from the University of California, Los Angeles. Before joining HDS, he served as Assistant Professor of South Asia Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Sevea is the author of Miracles and Material Life: Rice, Ore, Traps and Guns in Islamic Malaya (Cambridge University Press, 2020), which received the 2022 Harry J.Benda Prize, awarded by the Association of Asian Studies. Sevea also co-edited Islamic Connections: Muslim Societies in South and Southeast Asia (ISEAS, 2009). He is currently completing his second book entitled Singapore Islam: The Prophet's Port and Sufism across the Oceans, and is working on his third monograph, provisionally entitled Animal Saints and Sinners: Lessons on Islam and Multispeciesism from the East.

Sevea is the author of book chapters and journal articles pertaining to Indian Ocean networks, Sufi textual traditions, Islamic erotology, Islamic third worldism, and the socioeconomic significance of spirits, that have been published in journals such as Third World Quarterly, Modern Asian Studies, The Indian Economic and Social History Review and Journal of Sufi Studies. In addition to this, he is a coordinator of a multimedia project entitled “The Lighthouses of God: Mapping Sanctity Across the Indian Ocean,” which investigates the evolving landscapes of Indian Ocean Islam through photography, film, and GIS technology.