Insights into the Social Life of India’s Government Recruitment Examinations Coaching Industry

In January 2022, protests erupted across India after irregularities in the Railway Recruitment Board examination process left thousands of candidates uncertain about their futures. For many young people, the coveted and competitive entrance examinations remain a pathway to stable employment and social mobility. The 2022 protests underscored the political and social weight carried by test-based selection.

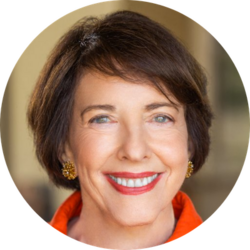

For Isabel Salovaara, a Ph.D. candidate in anthropology and a 2025-26 APARC predoctoral fellow, such moments reveal how examinations function as powerful governing mechanisms. Her research examines the vast ecosystem of private tutoring and coaching that has developed around competitive exams in India, asking how these industries shape youth aspirations, reproduce or mitigate inequality, and spur distinctive relationships to the state.

Salovaara identifies two core contributions of her project. “First, at an empirical level, I show how India’s coaching industry turns the individualizing, exclusionary mechanism of competitive examinations into an opportunity for connection – both to peers and to the state.” Although exams rank candidates against one another, exam preparation is a deeply social process. Aspirants share hostels, attend group classes, and form study networks, creating a sense of community within competition.

“At a theoretical level, I offer the figure of the ‘aspirant’ – the common label for these exam-takers in India – as a way of rethinking aspiration as a circular rather than linear process,” Salovaara says. Aspirants often make multiple “attempts,” apply for several different jobs, and sometimes continue preparing for higher-level exams even after securing a government post. “By illustrating this cyclical temporality, I argue that aspiration is less a one-time projection toward a fixed future than an ongoing, socially embedded practice of recalibrating possibilities.”

Salovaara’s interest in India’s exam culture began while teaching English at a community center in Delhi. She noticed that students preparing for competitive tests were falling behind in schoolwork; regular curricula rarely aligned with exam demands, encouraging reliance on private tutoring. Her research expanded from early fieldwork in coaching hubs such as Kota to government job preparation in Bihar.

High-stakes examinations in India determine entry into medical and engineering colleges, civil services, public sector banks, railways, and other state institutions. They operate on principles of relative merit: success depends not simply on passing, but on ranking above others. Merit is competitive and relational, intensifying pressure and uncertainty. In many urban centers, entire neighborhoods are organized around coaching institutes, with hostels, mess halls, internet cafés, and specialized academies serving aspirants seeking to “crack” exams.

APARC 2026-27 Predoctoral Fellowship Now Open to Applications

Sign up for APARC newsletters to receive our scholars' research updates >

From Tutoring to Coaching Economies

In Bihar, where industrial development is limited and private-sector jobs are scarce, government employment at nearly any level is highly prized for its stability and prestige. Salovaara traces the transformation of small-scale private tuitions into large commercial coaching enterprises that promise strategic mastery of overlapping “general studies” syllabi relevant to multiple government exams.

Despite the growth of the coaching industry, it remains a weakly regulated sector. One of the greatest challenges in studying it, Salovaara explains, is the lack of reliable data. She would like to document how many people participate in coaching and the demographic composition of student populations, including gender and caste. Yet coaching centers are often secretive about their records, and there is no centralized system of data collection comparable to state-run schools. Rigorous large-scale quantification is therefore nearly impossible.

Given these constraints, Salovaara’s work is primarily ethnographic. She has enrolled in online coaching courses, lived in student hostels, and trained in police recruitment academies. This approach reveals how coaching centers generate dense local economies: billboards advertise success rates, retired military personnel teach physical training, bureaucrats conduct mock interviews, and government scholarships sometimes subsidize private coaching. The boundaries between state and market become blurred in the tense ecosystem of exam preparation.

Education, Transformative Aspiration, and Inequality

A central question in Salovaara’s research concerns how exam preparation shapes individual relationships to the state. Coaching fosters powerful forms of self-identification. Aspirants imagine themselves as police officers, bureaucrats, or civil servants; uniforms symbolize dignity, belonging, and familial pride. For many, a government job represents not only economic security but moral recognition.

Young women, in particular, articulate transformative aspirations. Some describe their future positions as a way to elevate their families’ status or reshape gendered expectations. Exam success becomes a vehicle for reimagining inheritance and intergenerational recognition.

At the same time, the state appears as examiner and gatekeeper. It defines syllabi, sets evaluation criteria, and determines advancement. It is both a destination and an obstacle. When fairness is called into question, as in the 2022 railway protests, identification can quickly shift to anger. Examinations thus generate both attachment to and critique of state authority.

Salovaara’s research highlights how coaching spans socioeconomic categories, but sustained exam preparation requires significant financial investment. Families with greater resources can afford longer study periods and higher-quality instruction. For those with limited means, coaching represents a high-risk attempt to convert economic capital into secure employment. Aspirants may spend years in precarious living conditions with no guarantee of success. Many describe the industry as extractive, even as they remain committed to its promise of mobility.

Intellectual Community and Ongoing Questions

At APARC, Salovaara has been able to focus on writing while engaging in comparative conversations about education across the Asia-Pacific region. She describes enriching informal exchanges and discussions with postdoctoral fellows, particularly Taiwan Postdoctoral Fellow Ruo-Fan Liu, among others, about education and ethnographic research during the COVID pandemic.

After completing her Ph.D. this spring, Salovaara hopes to teach and continue her research. She is preparing a book manuscript, Exam Raj, which examines selection examinations as a mode of governance. Future projects include research on women in the police and on how alcohol prohibition policies contribute to the formation of female electoral constituencies in India.

She urges young scholars to look beyond their immediate field site and practice articulating the broader stakes of their work. Doing so, she says, helps clarify not only one’s argument, but also its significance.

Key Takeaways: Aspirations, Examinations, and the Indian State

- India’s coaching centers transform competitive exams into social worlds of connection as well as exclusion.

- Large-scale data collection on exam preparation is difficult to gather, elevating the importance of ethnography.

- Exam preparation produces both identification with and antagonism toward the Indian state.

- Selection examinations function as a central mode of contemporary governance.

Read More

Isabel Salovaara, APARC predoctoral fellow and a Ph.D. candidate in anthropology, examines how high-stakes examinations and the private tutoring industry in India shape youth aspirations and state relations.