Corporate Governance Faces New Reality in an Era of Geoeconomics

The optimistic assumptions that shaped the wave of globalization at the turn of the 21st century have given way to geoeconomics, also known as economic statecraft, or the use of economic leverage to advance the geopolitical interests of nation-states. In this environment of "weaponized interdependence," corporations have become actors on the frontlines of the U.S.-China rivalry, the Russia-Ukraine war, China-Taiwan tensions, and other national security conflicts in which they are organizationally ill-suited to play a central role, cautions APARC Faculty Affiliate Curtis J. Milhaupt, the William F. Baxter-Visa International Professor of Law and a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

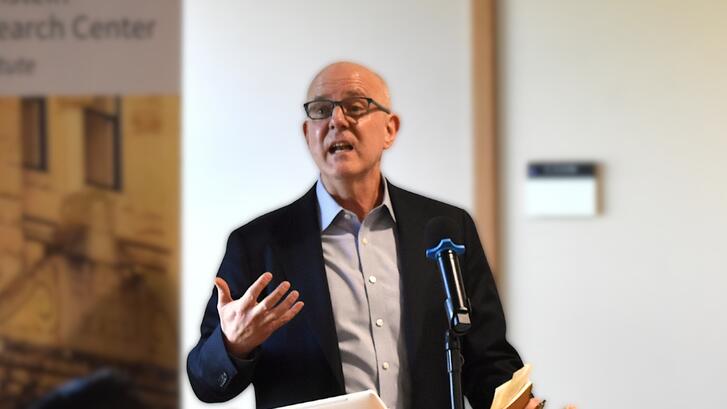

Milhaupt, an internationally recognized expert on comparative corporate governance, delivered a keynote speech titled Corporate Governance in an Era of Geoeconomics at the Corporate Governance Conference in Milan, Italy, on February 12, 2026. He described the era of geoeconomics as representing a dramatic departure from early 2000s thinking, when capital markets were viewed as politically neutral, shareholder identity was considered irrelevant, and scholars predicted global convergence on Western corporate governance models. All three assumptions have collapsed, posing significant repercussions for firm-specific legal risks and governance challenges. Watch Milhaupt's presentation:

Sign up for APARC newsletters to receive our experts' analysis >

Heightened Compliance Risk

The U.S.-China rivalry has created a particularly complex challenge for corporate governance, says Mihaupt. The United States has enacted multiple laws to curtail technology transfers to China, with China responding in a tit-for-tat fashion. The resulting, rapidly shifting and conflicting legal environment makes it "virtually impossible for a compliance department to comply with both U.S. and Chinese regulations."

Milhaupt introduced the concept of "ESG + G," adding geoeconomics to the Environmental, Social, and Governance framework used by investors and companies to assess a company's sustainability, ethical impact, and risk management beyond mere financial performance. Like ESG, geoeconomics involves corporations taking on roles traditionally played by governments. "I think in many respects private companies have become national security partners of their home country governments," he said.

Milhaupt's review of the disclosures of risk factors in the securities filings of public companies in the United States over the past 20 years shows the dramatic shift in corporate risk perception. Mentions of geopolitical risks related to export controls, the China-Taiwan conflict, and supply chain vulnerabilities have spiked sharply since 2020, with a particularly dramatic increase following Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Despite these challenges, corporations appear to be unprepared for the exploitation of the vulnerabilities created by economic interdependence in the era of geoeconomics. Only 5% of Russell 3000 companies disclose information on how they monitor geopolitical risk, Milhaupt finds. Among those that do, most provide no details about their strategies. Meanwhile, the expertise necessary for geopolitical risk assessment is declining as a percentage of S&P 500 boards of directors.

Divergent Governance Paths

In the era of globalization, corporate governance systems worldwide largely converged around the liberal vision of shareholder primacy. In today’s geoeconomic era, however, a different kind of convergence may be emerging: one shaped less by market ideology and more by the shared political values and strategic priorities of the home governments of globally active firms. Thus, we are witnessing increasing concern with the national identity of corporations and their shareholders, Milhaupt observes. "The standard legal tests for corporate national identity – jurisdiction of incorporation, or the real seat doctrine – are in danger of being overriden by political determinations such as the one that was applied to TikTok in the United States."

At the same time, Milhaupt argues, we may be witnessing the beginning of a movement in the opposite direction to the Western model of corporate governance: "the spread of what might be thought of as state capitalism in the West." To illustrate this trend, Milhaupt cites the case of the U.S. government's "golden share" in U.S. Steel as a condition for allowing its merger with Japanese company Nippon Steel.

While Milhaupt recognizes the necessity of government actions to protect national security in the corporate sector, he warns against ad hoc informal interventions in the private sector. "I don't think that these are really the answer to competition with Beijing," he said. "I'm particularly concerned about the impact of these government interventions on global investment, which relies on a predictable legal regulatory enforcement regime."

Milhaupt concludes that the era of geoeconomics is "the new normal," and both companies and governments must adapt to a world where economic and national security concerns are inextricably linked.

Read More

No longer insulated from statecraft, corporations have been thrust onto the front lines of geopolitical rivalry, while governance structures have not caught up, cautions Stanford Law Professor Curtis Milhaupt in a keynote speech delivered at the 2026 Corporate Governance Conference.