Fixing Intelligence Failures: The Last Shah, the United States, and the View from Somewhere

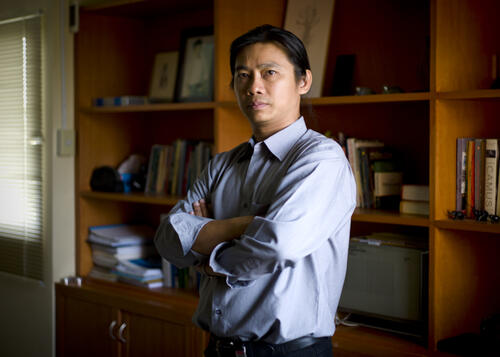

In a new article published in Intelligence and National Security, APARC South Asia Research Scholar Arzan Tarapore examines the sources of estimative failure, including the case of the 1979 Iranian revolution, and extends a potential solution to such failures through what he terms “the view from somewhere.” Tarapore suggests that estimative failures are the result of a flawed orthodoxy of intelligence-policymaker relations, which overlook the policymaker’s actual and potential impact on the target.

Sign up for APARC newsletters to receive our experts' research updates.

In contrast, Tarapore’s concept of “the view from somewhere,” which places the intelligence customer’s policy and preferences at the center of the intelligence problem, moves beyond the traditional intelligence-policy orthodoxy. Historically, the intelligence community aspires to a rich and objective understanding of the target, a neutral “view from nowhere,” which prescribes a separation, both institutional and analytic, between producers and consumers of intelligence. Tarapore suggests that some estimative failures – including the Iran case – are the result of “intelligence neglecting a critical variable in the analytic problem: the policymaker’s actual and potential impact on the target.”

Problems with Intelligence Orthodoxy

Using the case of Iran, Tarapore argues that estimates adopting the view from somewhere could have warned Washington of critical decision points while it still had leverage to act, explained how U.S. policy had inadvertently shaped the Shah’s ineffectual response to unrest, and assessed opportunities for effective policy alternatives. For Tarapore, the view from nowhere and its surrounding orthodoxy is driven by “a concern over politicization in its many forms – a concern that is fundamentally sound, but often overblown or applied dogmatically…in some cases this aspiration to a view from nowhere is itself the impediment to effective estimates.”

Tarapore rules out traditional explanations of estimative failure that suggest the fault lies with insufficient data collection, weak analysis, or unreceptive audiences. “While more data and better analysis would always be welcome, they may not materially reduce uncertainty; and explanations centering on the intelligence-policymaker relationship offer no systematic critique of the orthodoxy that keeps intelligence and policymakers at arm’s length,” he writes.

The danger of dogmatic adherence to a view from nowhere orthodoxy is that estimative assessments of the unfolding events offer little actionable insight to their policy customers when they do not take into account the policymaker’s actual and potential impact on the target. According to Tarapore, “sometimes the problem is not a simple case of customers ignoring intelligence advice, but a more fundamental flaw in the intelligence-policymaker orthodoxy, which limits the types of questions intelligence estimates address.” By explicitly accounting for customer’s actual and potential impact on the situation – in those cases where policymakers had some influence on the target – analysts would have better prepared customers for change.

Limits to the View

As with any intelligence or security concept, there are limits to the view from somewhere. First and foremost, this concept does not reduce uncertainty, Tarpore notes. Data collection and deft analysis using social science methods remain as critical elements of an effective intelligence enterprise. Another caveat is that bringing the customer to the center of the intelligence problem means that intelligence analysts must track two moving objects: the target and the customer. The desired end-states, priorities and other constraints of the customer are also dynamic – they will shift as a function of political evolution, bureaucratic arrangement, or other policy developments.

As with all intelligence advice, the intelligence community can only do so much to shape the customer’s views and prepare them for change. Policymakers, Tarapore argues, would be unwilling to act solely on the strength of early, uncertain warning signs. The view from somewhere, however, would have been a useful tool to sensitize customers to the risks of not changing course – that failing to even tentatively prepare for change could result in an even costlier policy catastrophe, as with the case of revolutionary Iran.

Read the article by Tarapore

Read More

Introducing a new conceptual framework for intelligence analysts, South Asia Research Scholar Arzan Tarapore offers an alternative to traditional intelligence-gathering axioms that helps explain the failure of U.S. assessments on the Iranian revolution and may benefit current policymakers in better leveraging intelligence to achieve strategic goals.