Where Medicine Meets Society: Richard Liang’s Quest to Advance Trans-Pacific Collaboration in Medical and Public Health Research

Where Medicine Meets Society: Richard Liang’s Quest to Advance Trans-Pacific Collaboration in Medical and Public Health Research

Spanning medicine, public health, and East Asian studies, Richard Liang’s rare academic path at Stanford has fueled collaborations that bridge research and policy across borders and disciplines.

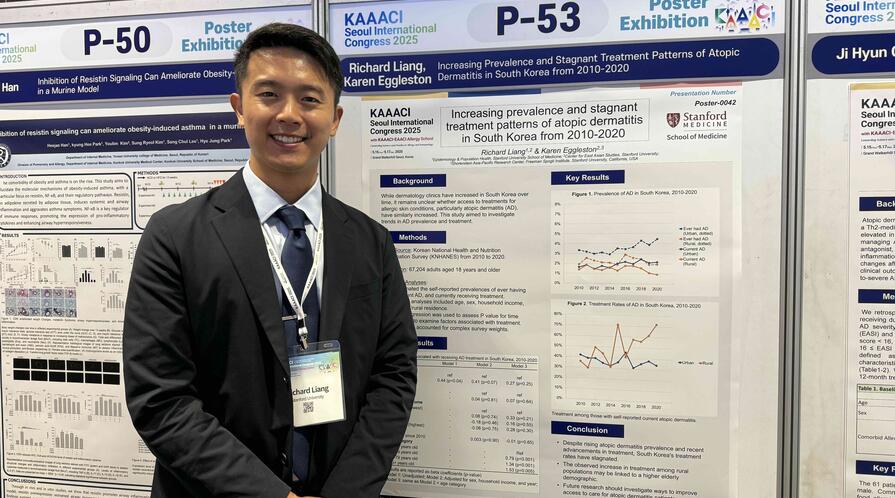

Stanford medical student researcher Richard Liang likes recalling how one summer project became a turning point in his academic career. What began as a study on disparities in South Korean patients’ access to diabetes care sparked a passion for collaboration in medical and public health research across East Asia and beyond.

Liang’s work with Stanford health economist Karen Eggleston, the director of the Asia Health Policy Program (AHPP) at the Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center (APARC) and his co-advisor for the Medical Scholars Research Program at the School of Medicine, helped deepen his global outlook. To bridge medicine, health policy, and his interest in East Asia, he embarked on one of the most ambitious paths at Stanford.

Selected into the rigorous and intensive Medical Scientist Training Program, he has been working toward his MD degree, with a scholarly concentration in health services and policy research in global health, while pursuing a doctorate in epidemiology and clinical research. This past June, he obtained his PhD from the Department of Epidemiology and Population Health. He is also completing a master’s degree in East Asian studies at Stanford’s Center for East Asian Studies, focusing on health and society in East Asia as well as the role of technology and academic partnerships in expanding access to care across the region.

“I aspire to become a leading physician-scientist who bridges that gap across borders and brings together researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to promote health and well-being in East Asia and around the world,” he says.

Sign up for APARC newsletters to receive our experts' updates >

Addressing Inequalities in Health Care

Liang’s summer medical school project examined the prevalence of receiving annual eye screenings among South Korean adult patients with type 2 diabetes and how access to that care differed across demographic and socioeconomic groups over time. The goal was to investigate why screening rates for diabetic retinopathy, a complication of type 2 diabetes, remain low in South Korea, despite the country having universal health insurance coverage and guidelines that recommend annual eye screenings to prevent this leading cause of blindness.

He worked on this project with co-advisors Eggleston and Young Kyung Do, a professor in Seoul National University’s Department of Health Policy and Management and AHPP’s inaugural postdoctoral fellow. They found that lower-income patients with diabetes experienced barriers to quality diabetes care and had lower access to annual diabetes-related eye screenings.

For Liang, these results underscored a deeper lesson: even strong health systems with universal health insurance coverage have structural socioeconomic inequities that leave vulnerable groups behind. The findings helped solidify his conviction that improving health care requires more than clinical training alone.

The project culminated in Liang’s presentation of the findings at the 2021 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting and spurred a new sense of purpose. ”It grew into a life-changing journey at Stanford,” Liang says.

That journey has led him to collaborate with researchers from around the world, particularly in Japan, Korea, and China, utilizing large-scale data to advance population health and applying population health methods to research topics ranging from maternal and child health to mental health, aging, and inflammatory skin diseases.

Liang in South Korea. Photo courtesy of Richard Liang.

From Research to Health Policy Impact

Over the years, Liang evolved from a mentee of Eggleston into a collaborator on projects in Korea and elsewhere. As COVID-19 disrupted health services worldwide, he joined Eggleston and a team of researchers in studying the impact of the pandemic on chronic disease care in India, China, Hong Kong, Korea, and Vietnam. Their findings showed that marginalized and rural communities in those countries were hit especially hard, with negative consequences for population health that reached far beyond those directly infected with the virus.

He and Eggleston also co-authored a study on preferences for telemedicine services among patients with diabetes and hypertension in South Korea during the early COVID-19 pandemic. The research drew the attention of the Prime Minister’s Office in Korea, which used it to guide national policy on telemedicine, a field still lacking a formal legal framework in the country.

For Liang, it was proof of the available opportunities to make tangible improvements in population health by combining rigorous research with policy engagement and drawing on insights across medicine, public health, and the social sciences.

“As a medical student researcher with experiences across different East Asian countries, I witnessed firsthand many pressing challenges in health and society, from rapidly aging populations to rising rates of chronic diseases,” he says. “To tackle these issues holistically, there is a growing need to bring together diverse perspectives, but regional collaborations in medical and public health research have been scarce, and rarer still between the biomedical and social sciences.”

Liang in China on a field visit during a 2025 summer seminar co-taught by Professors Eggleston and Williams. Photo courtesy of Richard Liang.

A Second Academic Home

Eggleston describes Liang as a model of interdisciplinary scholarship. In addition to medical school and doctoral research, he has carved out space to pursue his passion for East Asian studies. He has taken classes with APARC and affiliated faculty on topics ranging from health and politics in modern China to historical and cultural perspectives on North Korea, science and literature in East Asia, and tech policy, innovation, and startup ecosystems in Silicon Valley and Japan.

“The various classes and seminars I’ve attended through APARC, and subsequently as an East Asian Studies master’s student, have helped me think more critically about how the science and practice of medicine impact policy and society, and vice versa,” Liang says. Thanks to these experiences, he also found “a second academic home away from the medical school — a community that shares the recognition of the need to strengthen dialogue and cooperation across the Pacific and that actively encourages the interdisciplinary environment necessary to make my aspirations a reality.”

Most recently, he participated in a summer seminar on AI-enabled global public health and population health management, co-taught by Eggleston and Michelle Williams, a professor of epidemiology and population health at Stanford’s School of Medicine. Offered via the Stanford Center at Peking University, this three-week seminar focused on advancing global health through cross-cultural collaboration and the application of cutting-edge technology in population health and health policy decision-making.

“During this program, I not only got to share my experiences from conducting population health research across East Asia, but also learn from and alongside fellow students across different disciplines, spanning from international relations to computer science,” Liang notes. He especially enjoyed meeting local Chinese graduate students and providing feedback and near-peer mentorship as an upper-year graduate student.

The seminar also led to exploring additional opportunities for research collaborations to study the implications of long-term annual health screenings across China. Liang, Eggleston, and Williams plan to expand this collaborative work.

Preparing to Become a Better Care Provider

Liang’s work across borders and disciplines not only advances research but also deepens the perspective of cultural humility he brings to his future role as a physician.

“The cross-cultural experiences and fruitful academic exchanges I’ve learned through as a Stanford graduate student not only inform my research in different countries, but also help prepare me to become a better care provider for my future patients,” he says.

For his achievements, Liang has earned multiple honors, including a Young Investigator Collegiality Award from the International and Japanese Societies for Investigative Dermatology, the Critical Language Scholarship in Korean from the U.S. Department of State, and the Stanford Center for Asian Health Research and Education Seed Grant.

He is looking forward to finishing medical school, attending a residency program, and continuing an interdisciplinary career that advances human health and well-being.

Reflecting on the fleeting nature of student life, his advice to fellow students is to remember that “Your time as a Stanford student can really fly by, so make sure to explore the opportunities that speak to you and offerings across the university, by organizations like APARC and the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. The Bechtel International Center’s Office of Global Scholarships and the Hume Center for Writing and Speaking are also wonderful resources to get started.”

It is advice he has embodied himself, building a career at the intersection of medicine, public health, and East Asian studies, one project at a time.