As a new U.S. administration assumes office next year, it will face numerous policy challenges in the Asia-Pacific, a region that accounts for nearly 60 percent of the world’s population and two-thirds of global output.

Despite tremendous gains over the past two decades, the Asia-Pacific region is now grappling with varied effects of globalization, chief among them, inequities of growth, migration and development and their implications for societies as some Asian economies slow alongside the United States and security challenges remain at the fore.

Seven scholars from Stanford’s Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center (APARC) offered views on policy challenges in Asia and some possible directions for U.S.-Asia relations during the next administration.

View the scholars' commentary by scrolling down the page or click on the individual links below to jump to a certain topic.

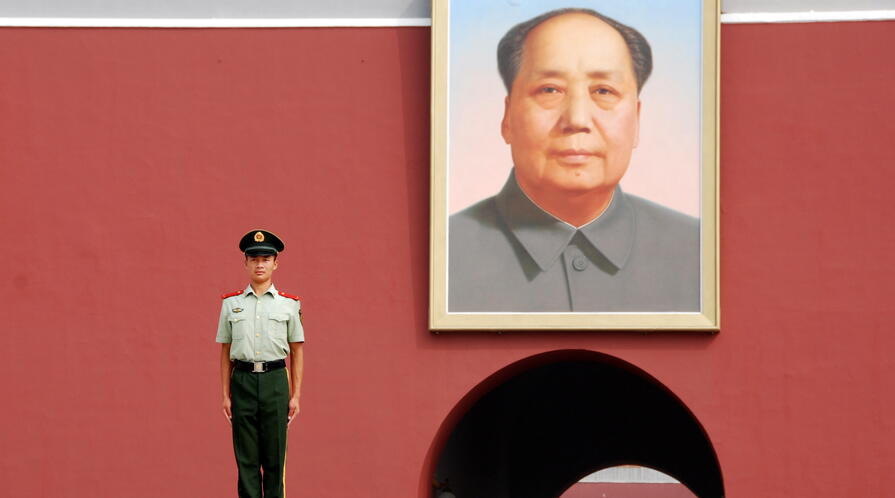

U.S.-China relations

U.S.-Japan relations

North Korea

Southeast Asia and the South China Sea

Global governance

Population aging .

Trade

U.S.-China relations

By Thomas Fingar

Managing the United States’ relationship with China must be at the top of the new administration’s foreign policy agenda because the relationship is consequential for the region, the world and American interests. Successful management of bilateral issues and perceptions is increasingly difficult and increasingly important.

Alarmist predictions about China’s rise and America’s decline mischaracterize and overstate tensions in the relationship. There is little likelihood that the next U.S. administration will depart from the “hedged engagement” policies pursued by the last eight U.S. administrations. America’s domestic problems cannot be solved by blaming China or any other country. Indeed, they can best be addressed through policies that have contributed to peace, stability and prosperity.

Strains in U.S.-China relations require attention, not radical shifts in policy. China is not an enemy and the United States does not wish to make it one. Nor will or should the next administration resist changes to the status quo if change can better the rules-based international order that has served both countries well. Washington’s objective will be to improve the liberal international system, not to contain or constrain China’s role in that system.

The United States and China have too much at stake to allow relations to become dangerously adversarial, although that is unlikely to happen. But this is not a reason to be sanguine. In the years ahead, managing the relationship will be difficult because key pillars of the relationship are changing. For decades, the strongest source of support for stability in U.S.-China relations has been the U.S. business community, but Chinese actions have alienated this key group and it is now more likely to press for changes than for stability. A second change is occurring in China. As growth slows, Chinese citizens are pressing their government to make additional reforms and respond to perceived challenges to China’s sovereignty.

The next U.S. administration is more likely to continue and adapt current policies toward China and Asia more broadly than to pursue a significantly different approach. Those hoping for or fearing radical changes in U.S. policy will be disappointed..

Thomas Fingar is a Shorenstein Distinguished Fellow and former chairman of the U.S. National Intelligence Council. He leads a research project on China and the World that explores China’s relations with other countries.

U.S.-Japan relations

By Daniel Sneider

U.S.-Japan relations have enjoyed a remarkable period of strengthened ties in the last few years. The passage of new Japanese security legislation has opened the door to closer defense cooperation, including beyond Japan’s borders. The Japan-Korea comfort women agreement, negotiated with American backing, has led to growing levels of tripartite cooperation between the U.S. and its two principal Northeast Asian allies. And the negotiation of a bilateral agreement within the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) talks brought trade and investment policy into close alignment. The U.S. election, however, brings some clouds to this otherwise sunny horizon.

Three consecutive terms held by the same party would certainly preserve the momentum behind the ‘pivot to Asia’ strategy of the last few years, especially on the security front. Still there are some dangers ahead. If Japan moves ahead to make a peace treaty with Russia, resolving the territorial issue and opening a flow of Japanese investment into Russia, that could be a source of tension. The new administration may also want to mend fences early with China, seeking cooperation on North Korea and avoiding tensions in Southeast Asia.

The big challenge, however, will be guiding the TPP through Congress. While there is a strong sentiment within policy circles in favor of rescuing the deal, perhaps through some kind of adjustment of the agreement, insiders believe that is highly unlikely. The Sanders-Warren wing of the Democratic party has been greatly strengthened by this election and they will be looking for any sign of retreat on TPP. Mrs. Clinton has an ambitious agenda of domestic policy initiatives – from college tuition and the minimum wage to immigration reform – on which she will need their support. One idea now circulating quietly in policy circles is to ‘save’ the TPP, especially its strategic importance, by separating off a bilateral Japan-U.S. Free Trade Agreement. Tokyo is said to be opposed to this but Washington may put pressure on for this option, leaving the door open to a full TPP down the road. .

Daniel Sneider is the associate director for research and a former foreign correspondent. He is the co-author of Divergent Memories: Opinion Leaders and the Asia-Pacific Wars (Stanford University Press, 2016) and is currently writing about U.S.-Japan security issues.

North Korea

By Kathleen Stephens

North Korea under Kim Jong Un has accelerated its campaign to establish itself as a nuclear weapons state. Two nuclear tests and multiple missile firings have occurred in 2016. More tests, or other provocations, may well be attempted before or shortly after the new American president is inaugurated next January. The risk of conflict, whether through miscalculation or misunderstanding, is serious. The outgoing and incoming administrations must coordinate closely on policy and messaging about North Korea with each other and with Asian allies and partners.

From an American foreign policy perspective, North Korea policy challenges will be inherited by the next president as “unfinished business,” unresolved despite a range of approaches spanning previous Republican and Democratic administrations. The first months in a new U.S. president’s term may create a small window to explore potential new openings. The new president should demonstrate at the outset that North Korea is high on the new administration’s priority list, with early, substantive exchanges with allies and key partners like China to affirm U.S. commitment to defense of its allies, a denuclearized Korean Peninsula and the vision agreed to at the Six-Party Talks in the September 2005 Joint Statement of Principles. Early messaging to Pyongyang is also key – clearly communicating the consequences of further testing or provocations, but at the same time signaling the readiness of the new administration to explore new diplomatic approaches. The appointment of a senior envoy, close to the president, could underscore the administration’s seriousness as well as help manage the difficult policy and political process in Washington itself.

2017 is a presidential election year in South Korea, and looks poised to be a particularly difficult one. This will influence Pyongyang’s calculus, as will the still-unknown impact of continued international sanctions. The challenges posed by North Korea have grown greater with time, but there are few new, untried options acceptable to any new administration in Washington. Nonetheless, the new administration must explore what is possible diplomatically and take further steps to defend and deter as necessary. .

Kathleen Stephens is the William J. Perry Distinguished Fellow and former U.S. ambassador to the Republic of Korea. She is currently writing and researching on U.S. diplomacy in Korea.

Southeast Asia and the South China Sea

By Donald K. Emmerson

The South China Sea is presently a flashpoint, prospectively a turning point, and actually the chief challenge to American policy in Southeast Asia. The risk of China-U.S. escalation makes it a flashpoint. Future historians may call it a turning point if—a big if—China’s campaign for primacy in it and over it succeeds and heralds (a) an eventual incorporation of some portion of Southeast Asia into a Chinese sphere of influence, and (b) a corresponding marginalization of American power in the region.

A new U.S. administration will be inaugurated in January 2017. Unless it wishes to adapt to such outcomes, it should:

(1) renew its predecessor’s refusal to endorse any claim to sovereignty over all, most, or some of the South China Sea and/or its land features made by any of the six contending parties—Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Vietnam—pending the validation of such a claim under international law.

(2) strongly encourage all countries, including the contenders, to endorse and implement the authoritative interpretation of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) issued on July 12, 2016, by an UNCLOS-authorized court. Washington should also emphasize that it, too, will abide by the judgment, and will strive to ensure American ratification of UNCLOS.

(3) maintain its commitment to engage in publicly acknowledged freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) in the South China Sea on a regular basis. Previous such FONOPs were conducted in October 2015 by the USS Lassen, in January 2016 by the USS Wilbur, in May 2016 by the USS Lawrence, and in October 2016 by the USS Decatur. The increasingly lengthy intervals between these trips, despite a defense official’s promise to conduct them twice every quarter, has encouraged doubts about precisely the commitment to freedom of navigation that they were meant to convey.

(4) announce what has hitherto been largely implicit: The FONOPs are not being done merely to brandish American naval prowess. Their purpose is to affirm a core geopolitical position, namely, that no single country, not the United States, nor China, nor anyone else, should exercise exclusive or exclusionary control over the South China Sea.

(5) brainstorm with Asian-Pacific and European counterparts a range of innovative ways of multilateralizing the South China Sea as a shared heritage of, and a resource for, its claimants and users alike. .

Donald K. Emmerson is a senior fellow emeritus and director of the Southeast Asia Program. He is currently editing a Stanford University Press book that examines China’s relations with Southeast Asia.

Global governance

By Phillip Y. Lipscy

The basic features of the international order established by the United States after the end of World War II have proven remarkably resilient for over 70 years. The United States has played a pivotal role in East Asia, supporting the region’s rise by underpinning geopolitical stability, an open world economy and international institutions that facilitate cooperative relations. Absent U.S. involvement, it is highly unlikely that the vibrant, largely peaceful region we observe today would exist. However, the rise of Asia also poses perhaps the greatest challenge for the U.S.-supported global order since its creation.

Global economic activity is increasingly shifting toward Asia – most forecasts suggest the region will account for about half of the global economy by the midpoint of the 21st century. This shift is creating important incongruities within the global architecture of international organizations, such as the United Nations, International Monetary Fund and World Bank, which are a central element of the U.S.-based international order and remain heavily tilted toward the West in their formal structures, headquarter locations and personnel compositions. This status quo is a constant source of frustration for policymakers in the region, who seek greater voice consummate with their newfound international status.

The next U.S. administration should prioritize reinvigoration of the global architecture. One practical step is to move major international organizations toward multiple headquarter arrangements, which are now common in the private sector – this will mitigate the challenges of recruiting talented individuals willing to spend their careers in distant headquarters in the West. The United States should join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, created by China, to tie the institution more closely into the existing architecture, contribute to its success and send a signal that Asian contributions to international governance are welcome. The Asian rebalance should be continued and deepened, with an emphasis on institution-building that reassures our Asian counterparts that the United States will remain a Pacific power. .

Philip Y. Lipscy is an assistant professor of political science and the Thomas Rohlen Center Fellow. He is the author of the forthcoming book Renegotiating the World Order: Institutional Change in International Relations (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Population aging

By Karen Eggleston

Among the most pressing policy challenges in Asia, U.S. policymakers should bear in mind the longer-term demographic challenges underlying Asia’s economic and geopolitical resurgence. East Asia and parts of Southeast Asia face the headwinds of population aging. Japan has the largest elderly population in the world and South Korea’s aging rate is even more rapid. By contrast, South Asian countries are aging more gradually and face the challenge of productively employing a growing working-age population and capturing their “demographic dividend” (from declining fertility outweighing declining mortality). Navigating these trends will require significant investment in the human capital of every child, focused on health, education and equal opportunity.

China’s recent announcement of a universal two-child policy restored an important dimension of choice, but it will not fundamentally change the trajectory of a shrinking working-age population and burgeoning share of elderly. China’s population aged 60 and older is projected to grow from nearly 15 percent today to 33 percent in 2050, at which time China’s population aged 80 and older will be larger than the current population of France. This triumph of longevity in China and other Asian countries, left unaddressed, will strain the fiscal integrity of public and private pension systems, while urbanization, technological change and income inequality interact with population aging by threatening the sustainability and perceived fairness of conventional financing for many social programs.

Investment in human capital and innovation in social and economic institutions will be central to addressing the demographic realities ahead. The next administration needs to support those investments as well as help to strengthen public health systems and primary care to control chronic disease and prepare for the next infectious disease pandemic, many of which historically have risen in Asia. .

Karen Eggleston is a senior fellow and director of the Asia Health Policy Program. She is the editor of the recently published book Policy Challenges from Demographic Change in China and India (Brookings Institution Press/Shorenstein APARC, 2016).

Trade

By Yong Suk Lee

Trade policy with Asia will be one of the main challenges of the new administration. U.S. exports to Asia is greater than that to Europe or North America, and overall, U.S. trade with Asia is growing at a faster rate than with any other region in the world. In this regard, the new administration’s approach to the Trans-Pacific Partnership will have important consequences to the U.S. economy.

Anti-globalization sentiment has ballooned in the past two years, particularly in regions affected by the import competition from and outsourcing to Asia. However, some firms and workers have benefited from increasing trade openness. The U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement of 2012, for example, led to substantial growth in exports in the agricultural, automotive and pharmaceutical sectors. Yet, there are winners and losers from trade agreements. Using an economist’s hypothetical perspective, one would assume firms and workers in the losing industry move to the exporting sector and take advantage of the gains from trade. In reality, adjustment across industries and regions from such movements are slow. Put simply, a furniture worker in North Carolina who lost a job due to import competition cannot easily assume a new job in the booming high-tech industry in California. They would require high-income mobility and a different skill set.

Trade policy needs to focus on facilitating the transition of workers to different industries and better train students to prepare for potential mobility in the future. Trade policy will also be vital in determining how international commerce is shaped. As cross-border e-commerce increases, it will be in the interest of the United States to participate in and lead negotiations that determine future trade rules. The Trans-Pacific Partnership should not simply be abandoned. The next administration should educate both policymakers and the public about the effects of trade openness and the economic and strategic importance of trade agreements for the U.S. economy.

Yong Suk Lee is the SK Center Fellow and deputy director of Korea Program. He leads a research project focused on Korean education, entrepreneurship and economic development.