Visiting fellow draws plan to scale up health index in China

Visiting fellow draws plan to scale up health index in China

China was for hundreds of years almost entirely an agricultural society, but modern industrialization changed that dynamic, and the impact on health has been startling.

Urbanization, population aging and changes in lifestyle (from mobile to sedentary) have led a transition from an acute to chronic disease-ridden society. Now, 10 percent of China’s adult population is diabetic or pre-diabetic—holding the number one place in the world.

Feng Lin and a team of researchers want to change that reality.

Lin is part of the Corporate Affiliates Program at the Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center. A visiting fellow, Lin leads a research project focused on innovations in primary health care systems in China, a topic that is also the core of his work at ACON Biotechnology. Throughout his research, Lin has worked with health policy expert Karen Eggleston.

“Thirty to forty years ago, people were talking about infectious disease,” Lin says, referring to Chinese society. “Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like diabetes didn’t even register. They were like the black sheep in the flock.”

Now, though, Lin says that China has reached a critical stage. NCDs have a noticeable presence, and the challenge for China is to create an effective healthcare system to serve its population of 1.3 billion. Its health delivery systems are not equipped to address and prevent diseases at such a high demand.

Lin believes that improving access to care by increasing the relevance of community health care centers, improving the quality of care and integrating IT infrastructure could provide pathways forward.

In pursuit of this, he is part of the team developing an open source health index with Yaping Du, a professor at Zhejiang University, and Randall Stafford, a professor of medicine at the Stanford Prevention Research Center.

The index is one of many activities that Lin is involved with at Stanford. Forging a new type of partnership with the Asia Health Policy Program, his company sponsored a public seminar series this past year.

Restructuring quality care

Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Determining how to restructure China’s healthcare system is a tough challenge because it’s a bureaucratic hierarchy – multiple divisions traverse each province, prefecture, township and village.

In 2009, the Chinese government laid out aggressive reforms to its healthcare policy. Lin says he believes the most essential part of that plan is the empowerment of grassroots-level community healthcare centers.

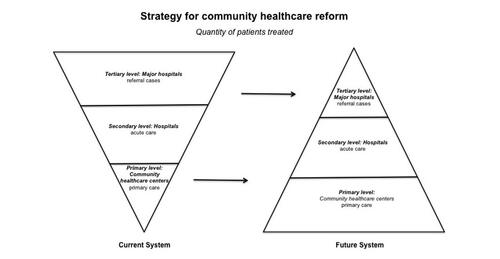

“You cannot just deal with primary level, you must look at the secondary and tertiary segments, too—a whole system approach,” he says.

Resembling a pyramid, China’s system has a finite number of top physicians who are mostly located at major hospitals. Patients who pursue services are likely to go to major hospitals in urban areas, instead of their local health community centers. About 90 percent of health care is delivered in hospitals—leading to overcrowding. Moreover, patients choose to self-treat or self-medicate which can lead to misdiagnosis.

Collecting data in Hangzhou, a coastal city just south of Shanghai (shown in map photo), Lin discovered that these trends could be explained by two reasons.

Patients have a low level of trust in community health centers, and local facilities lack capacity (e.g. having only 20 bed spaces) and expertise (e.g. employing medical personnel with sometimes outdated training). His analysis reinforced earlier outcomes found by Karen Eggleston.

Lin says the solution lies in increasing access to highly skilled physicians and organizing the system more efficiently.

Comparing China to the United States, Lin believes community healthcare centers should become main hubs for service delivery. The centers would operate as the first and last touchpoint for patient care, like “gatekeepers” in the U.S. system, administering advanced services and prevention programs like wellness education.

And while local centers are becoming more prevalent—China has more than 34,081 centers—development isn’t fast enough, not enough physicians exist, and patients aren’t actively choosing to redirect their services to community healthcare centers.

Courtesy: Feng Lin

Courtesy: Feng Lin

Figure 1. Strategy for community healthcare center reform advocates "strength at the grassroots." Currently patients seek care at major hospitals as their first stop, but in the future system, patients will go primarily to grassroots community healthcare centers. Courtesy: Feng Lin

Creating ease

Chinese people are typically leery of the quality of health care available at community healthcare centers, and overcoming that trust deficit won’t be an easy task. However, Lin says it’s a matter of informing citizens about local services and training more physicians to deliver quality care.

To address quality concerns, the Chinese government has set out to expand medical training programs. Enhancing the expertise of current and future physicians in rural community healthcare centers is essential, Lin says.

The health index aims to empower patients so that they can determine the best medical accommodation available, and also create a mechanism that rewards good work.

The key is to create a participatory system, one that incentivizes the patient and the physician, he says.

Hosted digitally and in the public domain, the index will list all physicians throughout Zhejiang province. Patients and healthcare professionals can login and share their experience, providing a “satisfaction rating” of hospitals and community health care centers.

Beyond external contributions, the index will support data provided by China’s national Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and local centers for disease control, to include mortality rate and cause of death and many other indicators sourced from publicly available data.

“It will build up a kind of system that people can trust – something that people can rely on,” Lin says.

Similar platforms have been implemented in advanced industrialized nations. Lin hopes that the index will offer a model that could be applied nationwide.

“It’s nearly impossible to have a single policy apply,” he says. “But, if there’s a success in one area or a few areas, the central government will pick up that approach.”

Lin expects that his team will unveil the pilot program at a conference on general practice in October 2015. The conference aims to provide practical ways to improve primary care services and the education and training of general practitioners.

Map shown above is Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons