Gi-Wook Shin: Why Japan cannot ignore Beijing's 'charm offensive' toward Seoul

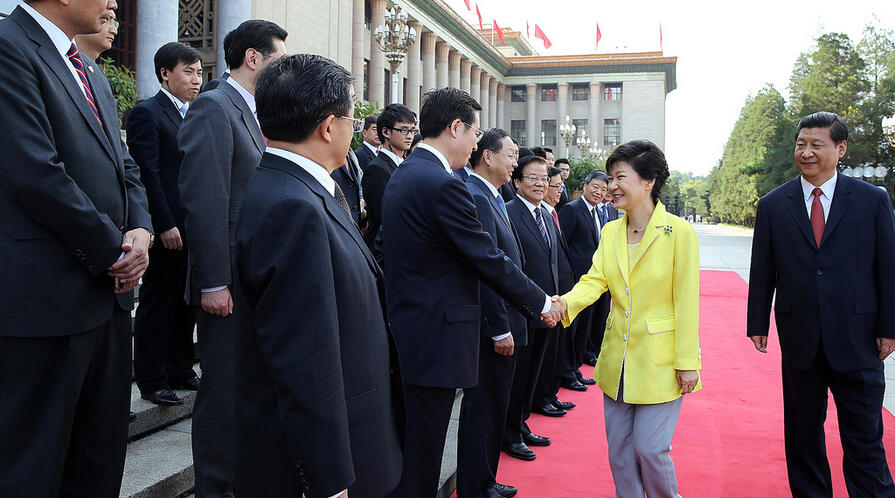

With tensions between Japan and South Korea continuing over historical and territorial issues, Beijing is more than willing to use the history card to woo Seoul. In a recent visit to South Korea, Chinese President Xi Jinping said that "in the first half of the 20th century, Japanese militarists carried out barbarous wars of aggression against China and South Korea, swallowing up Korea and occupying half of China." Earlier this year, China opened an elaborate memorial hall in Harbin to honor Ahn Jung-geun, who killed Hirobumi Ito, the first Japanese resident-general of Korea. To Koreans, Ahn is a national hero; to Japanese, a terrorist. Xi's visit to Seoul was to repay South Korean President Park Geun-hye's own visit to Beijing last year. Neither Park nor Xi has visited Tokyo yet.

China is apparently seeking to pull South Korea over to its side in its widening strategic competition with the United States and Japan. Xi's "charm offensive" toward Seoul is based on the calculation that South Korea's strategic value will only increase in coming years.

For South Korea, there are compelling reasons to improve relations with China. Ties had been strained by Park's predecessor, Lee Myung-bak, emphasizing South Korea's alliance with the U.S. She must take into account that China is becoming ever more important to South Korea's economy. (Apart from Taiwan, South Korea enjoys the world's largest merchandise trade surplus with China, approaching $100 billion). Park also wants China to support her North Korea policy focused on ending Pyongyang's nuclear weapons program and preparing for unification.

While China actively asserts its claim to leadership in Northeast Asia in courting South Korea, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe seems to deliberately ignore, if not dismiss, the importance of South Korea. Japanese policymakers argue, wrongly, that the Park government is "pro-China" and that Japan needs only to worry about China itself. Conservative Japanese media regularly bash the South Korean government and South Korea more broadly, and anti-Korean sentiments in Japan are on the rise.

Japanese focus is understandably on its alliance with the United States. But American policymakers openly worry that continuing tensions between its main allies in the region will undermine its strategic position regarding China and North Korea. President Barack Obama brought Abe and Park together in March on the sidelines of the Nuclear Security Summit, but with little to show for it. The United States is also concerned that the Abe government's nontransparent dealings with North Korea on the abductee issue could further damage Japanese-South Korean relations and vitiate U.S. efforts to press Pyongyang on the nuclear issue.

Northeast Asia is in flux. With its economic and military power growing, China is seeking to regain the dominant position in the region that it ceded to Japan over a century ago. In the process of reshaping a regional order, the Korean Peninsula will again be very important. Already, two major wars occurred over Korea when old and new powers competed for hegemony -- the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. It is crucial for both Japan and South Korea to maintain friendly relations with a rising China, but it is just as important that they improve their own bilateral relationship. Both have much to lose if the current trajectory in the region is not corrected. Moreover, Japan and South Korea have much in common, from their social and economic systems to democratic values, much more in fact than either has with China.

So, what should be done? Above all, both Japan and South Korea must work much harder to resolve the issues that continue to arise out of their shared history of colonial rule and war. South Korea needs to move beyond victim consciousness, and Japan needs to show more farsighted political leadership. Specifically, Japan should unequivocally reaffirm the Kono Statement regarding the "comfort women" issue, and Abe should make it clear that he won't visit Yasukuni Shrine again during his tenure as prime minister.

The 1993 statement was a key marker on the history question for South Koreans; the recent review of it sent the wrong message to Koreans. Japanese leaders are certainly entitled to honor those who sacrificed their lives for their country, but paying tribute also to convicted war criminals is an entirely different matter -- not only in the eyes of South Koreans but also of the international community as a whole. For its part, Seoul should make clear how much it values good relations with Japan and state that it is ready to work with Tokyo in a constructive fashion to fully and finally resolve the remaining historical issues.

Next year will be the 50th anniversary of the normalization of relations between Japan and South Korea. It should be an occasion to celebrate what that has meant for both countries -- regional peace and stability and economic prosperity. But even more importantly, both Tokyo and Seoul should also use the anniversary as a golden opportunity to develop a new vision for their relationship. The future of Northeast Asia will be brighter for all the countries in the region if its two major democracies show greater wisdom.

Gi-Wook Shin is a professor of sociology and director of the Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center (APARC) at Stanford University. Shin's article (with Daniel Sneider, the associate for resarch at Shorenstein APARC), "History Wars in Northeast Asia," appeared in Foreign Affairs (April 2014).

This article was originally carried by Nikkei Asian Review on 17 Sept. and reposted with permission.